Strategies for Helping Kids Remember What They Read Using Stickies

Supporting meaningful conversations among young children can be challenging but is well worth the effort. Many studies have demonstrated the importance of developing speaking and listening skills in early babyhood (Hall 1987; Clay 1991; Kirkland & Patterson 2005). Every bit part of a collaborative study, we—a firstgrade teacher and two university-based researchers—prepare a goal to facilitate meaningful, student-led discussions well-nigh literature. Nosotros began by having students bring books to whole- and small-scale-group activities and encouraging them to talk. While this was a good showtime, we quickly realized that the children needed back up to learn how to interact appropriately during conversations that were not led by the teacher. Figuring out what types of supports would be effective became the heart of our written report.

In this commodity we share several strategies that we found successful in enhancing the speaking and listening skills of a course of 28 first graders. The children— who came from diverse linguistic, economic, and social backgrounds—began the school year with below average to boilerplate literacy skills. Meridith, the teacher (and second writer), had 12 years of teaching experience; throughout the yearlong study, she acted as both a researcher and a participant, trying out and reflecting on each of our instructional ideas.

Advert

Nosotros wanted to aid the children develop the ability to have meaningful conversations about books without needing Meridith's guidance. Our goal was for the children to collaboratively construct interpretations of texts through group discussions. Discussion increases students' date, helps them take responsibility for their learning, prompts higher-level thinking, offers room for clarification, encourages children to build and share noesis, and gives them opportunities to apply comprehension strategies (Kelley & Clausen- Grace 2013). Nosotros aimed to create an environment where children could scaffold each other's learning (Johnston 2004) through talk. Knowing that research has demonstrated that discussion supports comprehension (Wells 1999; Nystrand 2006), we ready out to teach young children to engage in such exchanges.

Give-and-take also offers the benefit of being inclusive of students from various backgrounds. Previous work has institute that discussion increases participation for dual language learners and reading enjoyment for all (Carrison & Ernst-Slavit 2005), and that conversations enable teachers to publicly value all students' thinking and talk.

However, powerful literary discussions do non emerge naturally in the primary grades. Inquiry and our experiences have identified the need for teacher back up (Baker, Dreher, & Guthrie 2000) through methods such every bit explicitly didactics children the social skills necessary for conversation (Harvey & Daniels 2015), teaching students to talk to each other without relying on the teacher (Serafini 2009), and providing time for children to prepare and reflect (Kelley & Clausen-Grace 2013).

In addition to the academic, social, and motivational benefits of literature discussions, the Common Core Land Standards (NGA & CCSSO 2010) reinforce the importance of teachers devoting time to enhancing children's speaking and listening skills. Speaking and listening standards are part of the Common Core Language Arts Standards for each form. Through our report, we expected to address the following standards, which focus on collaborative talk, following discussion norms, adding to the contributions of others, and asking questions:

- SL.1.1: Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about grade ane topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups.

- SL.1.i.A: Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.thou., listening to others with care, speaking one at a time about the topics and texts under discussion).

- SL.i.i.B: Build on others' talk in conversations by responding to the comments of others through multiple exchanges.

- SL.1.1.C: Ask questions to clear up any confusion about the topics and texts under discussion.

Fostering pupil-led discussions

From the start of the year, Meridith taught speaking and listening in academic contexts. She supported children in listening to and learning from each other, preparing for discussions, and taking responsibility for discussions.

Teacher support for speaking and listening

Meridith provided explicit instruction in speaking and listening. Commencement, she focused on teaching students to listen. She offered explanations, modeled appropriate behaviors, and gave children fourth dimension to practise sitting upward, resisting distractions, and looking at the speaker. When students struggled to stay focused, she gently encouraged the speaker to suspension until all the students were looking. In the following transcript from a fall classroom observation, Meridith provided explicit education about how to listen during whole-group discussions:

Meridith: If you lot're touching and playing with your book, it'southward hard to listen to the person who'south speaking. Information technology ways the speaker volition have to expect for you to be a respectful listener, reader, and friend. And then, if y'all want to share, your hands should be off your book. I desire yous looking at the person talking. You lot have to await until that person is finished to put your own opinion in.

Meridith also offered more subtle speaking and listening support past calling attention to conversational norms—like proverb, "I hear Jorge talking," when another student was almost to interrupt—and using nonverbal cues, like middle contact and pointing, to remind children of expectations.

Meridith'due south reflection

At the first of every year, I envision students independently engaging in meaningful discussions while I take notes and think about how these grand conversations will guide my instruction. And then I remember it is August and they are half-dozen. Starting with nuts—such every bit torso language, conversational turns, and voice project—helps prepare the tone for future discourse. While it seems simple, and we often assume children have already internalized these skills, many have not. Investing time in explicitly didactics basic chat skills allows children to be more independent and become deeper with their thoughts.

Children's responsibilities in discussions

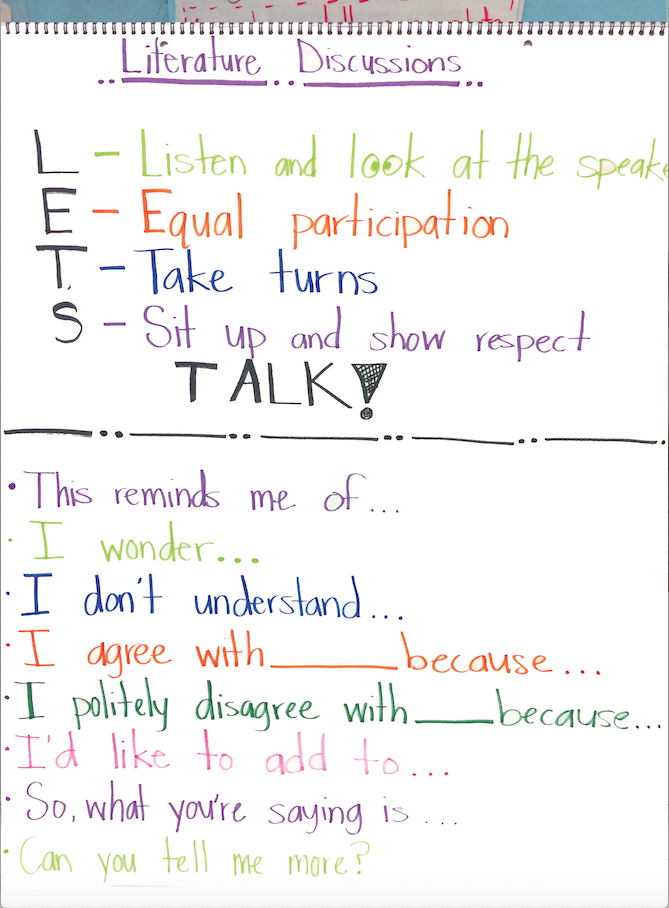

Meridith taught students to take ownership of discussion norms. She expected children to look until there was silence and eye contact from anybody earlier they started to talk. If children began speaking before listeners were ready, she would remind them to get the attention of the audience. For instance, she taught them to utilise a cue—saying, "Class, class," and waiting for the other students to answer, "Yeah, yes?"—before continuing the discussion (Biffle 2013). She had students have responsibility for calling on each other, including recognizing who yet needed to participate in the conversation. Meridith also taught them the language frame "Questions, comments, or connections?" to generate give-and-take and responses. (For additional language frames that supported word, run across the photo "Literature Discussions Anchor Chart.")

The children needed practice to internalize these norms, as the following observation shows.

Meridith: Brandi, do y'all desire to say something to Logan at this time?

Brandi: Will yous please finish, Logan? 'Cause I'm trying to say something, and you keep on interrupting me and doing funny stuff considering anybody's looking at you. Then, can you delight exist really serious in the grouping?

(Logan puts his head down on the table, as if upset.)

Brandi: I don't mean like put your caput down.

(Logan sits up.)

Meridith'due south reflection

Putting ability in the hands of the students produced one of their greatest transformations because it held them accountable and fabricated them leaders. Information technology was an initiative to steer them away from the traditional classroom discourse in which teachers ask questions and students raise their easily to respond. The children quickly learned that I was not the but one who had power. Encouraging students to ask each other for questions, comments, or connections helped them move conversations frontwards without my support. Those iii words were a goad for collaborative conversations every bit children discovered their classmates had ideas to share and that a conversation was a two-way street.

Discussion preparation

Meridith emphasized that students needed to come up to the class'southward literature discussions prepared. She provided common texts alee of time, with the expectation that children would read them and tape their thinking (things learned, questions wondered, and personal connections) on sticky notes (Moses, Ogden, & Kelly 2015). During breezy 1-on-one conferences that Meridith regularly had with each child, they discussed their thoughts on the texts and which ones would exist good topics to bring up at the group discussion. When students came together, they had comments and questions ready.

In the following commutation from the spring, Meridith explored with the class why thinking virtually the text beforehand is helpful for word.

Meridith: I want you to reread your literature discussion book, stop and think, and apply your stickies. If nosotros're not stopping and thinking while nosotros're reading, when nosotros come up to a literature discussion, are we going to have a lot to say?

Orin: You tin't only be similar, if you brought Henry and Mudge's Big Sleepover, "Well, information technology was nearly Henry and Mudge and a big sleepover." You tin can't only say that.

Meridith: Is that a very exciting conversation?

Class: No.

Meridith: And then, your conversation needs to be . . .

Bianca: Bigger.

Meridith: Interesting and bigger, I like the manner you said that. And one of the means we reach that is past using our sticky notes and thinking.

Meridith'due south reflection

Initially, I thought stickies might interfere with the children's reading and thinking. I feared they would focus on spelling or the process of writing rather than on generating thoughtful ideas to share. I was wrong. As I introduced and modeled different uses for stickies, my students used them with not bad intent. It gave them purpose while reading and something to share during discussion (Kelly & Moses 2018). Information technology is non always easy to call up on the spot—sticky notes helped us collect our thoughts before participating, enabling students to voice their ideas and be heard and valued.

Gradually increasing children's independence

Meridith first taught speaking and listening in the context of turn and talk and whole-group discussions. As students gained independence, they moved into instructor-scaffolded small-group discussions and later small-grouping discussions with minimal adult support.

Plough and talk

Meridith used turn and talk in a variety of settings— such every bit during morning message and lessons—non only in literature discussions. For turn and talk, she asked an open up-ended question and gave the children two to three minutes to hash out it with their assigned partner. (To increment children's comfort but still avert partnering children only with their shut friends, Meridith assigned long-term plow-and-talk partners.) Meridith then called the students dorsum together and asked them to share their thinking and what they learned from their partners.

Discussion increases students' appointment, helps them take responsibility for their learning, and prompts college-level thinking.

To make turn and talk successful, Meridith started working with students at the beginning of the year to ensure they knew the basics of how to talk and mind. She emphasized the importance of physically turning to face partners and of making middle contact. To encourage engaged listening, Meridith often asked students to retell what their partners had said. In this transcript from the get-go of the year, Meridith modeled asking questions, provided explicit instruction in speaking and listening, and checked in with unlike student groups.

Meridith: Remember, you desire to exist looking that person in the centre, directly forward. (Brief pause.) At present, ready? Ask the question. Start with, "How was your weekend?" (Students talk.)

Meridith: You were all chitter-chattering very nicely. I saw you looking each other in the eye, listening. I saw some heads nodding.

(Meridith engages Kelsey in conversation). Kelsey shares that she had a good weekend. Meridith asks what she did and whom she saw. After Kelsey answers, Meridith asks, "Annihilation else special?" Kelsey talks most a cake. Meridith asks, "What kind?," and makes centre contact as she listens to Kelsey's answer.

Meridith: (Turning to the whole class.) Do you meet how I asked some questions? Could yous ask your friends some questions like that when yous're turning and talking? If your friend doesn't give you a lot of data, then ask some more questions.

Meridith's reflection

Turn and talk helped children work on their conversational skills on a minor scale. They were expected to apply eye contact, responsive body linguistic communication, and engaged listening with only ane person. For many, especially dual language learners, this was the to the lowest degree intimidating conversation type. Having a consequent plow and talk partner helped build strong relationships; equally time progressed, partners opened up more than. They learned to ask questions, have conversational turns, and add together to each other'due south thoughts.

Whole-group literature discussion

In August, students began sharing their thinking about books they each had called and read independently, something they connected to work on throughout the twelvemonth. To support children in engaging in these discussions, Meridith gave them a clear framework: One student would share about a book while the others listened. The class knew it was their turn to respond when the presenting student asked, "Questions, comments, or connections?"

Every bit this transcript shows, Meridith provided specific instruction on expected listening behaviors during a literature circle after in the year:

Meridith: We want to show our friends that nosotros intendance about what they have to say. If you're flipping through the pages, it doesn't show your friends that you intendance well-nigh the information that they learned in their books. When your friend is speaking, you lot're giving them eye contact.

Meridith'due south reflection

Whole-group literature discussions were definitely the virtually challenging. Getting 28 commencement-graders to care about what each had to say seemed overwhelming; but we kept reviewing listening and speaking expectations, and over time the discussions transformed. Implementing "Questions, comments, or connections?" and utilizing glutinous notes helped take whole-group discussions to the next level. Students started to run into the value in whole-grouping discussions as the discussions became a forum for sharing and recommending books.

After the children learned the norms of whole-group literature discussions, they began small-group discussions most a book they had all read. These discussions required sustained adult back up to move forward and stay on topic; teachers also ensured that all students had a plough to speak and that multiple students didn't share at the same fourth dimension.

In this springtime classroom observation, Meridith guided Evan in order to help him and the other grouping members larn how to facilitate their own word with less adult support.

Meridith calls on Evan. She tells him to await until he has anybody's optics on him. He announces whose optics he'south still waiting for. Meridith prompts him to say, "Excuse me." He says, "Alibi me, Brook," and once Beck looks upward, Evan starts reading aloud his connectedness about a time when he was stubborn.

Meridith's reflection

Small-group literature discussions were my favorite because they were full of free energy. The children loved discussing a common text. At offset, they were so excited they often spoke over each other before a student's thoughts were complete. Because of this, nosotros modeled constructive conversation insertions and provided explicit instruction and language frames to help children get back on track. We also found that literature discussion groups were easier to manage with no more than 5 students.

Less-guided small-group literature discussion

Although the first graders made slap-up strides toward independence and required much less scaffolding as the year progressed, they did not develop the ability to agree deep, on-topic literary discussions without developed back up. With exercise, notwithstanding, they internalized discussion norms, took responsibility for moving literature discussions forward, and used strategies for keeping their peers focused (Moses, Ogden, & Kelly 2015).

In the following late jump observation, Eloise helped Alexis identify and understand the author's bulletin in a story.

Eloise: Oh, I got a good author'south message at the end.

Alexis: What! In that location's an writer'southward bulletin?

Eloise: Yes. This is in the back too. If someone . . . If someone is being hateful, really try difficult. Ask, If I were you, so what you lot want me to exercise? Make you lot clean upwardly my mess? Treat others the way y'all want to exist treated.

Alexis: I didn't know there was an author's message.

Meredith'due south reflection

Alexis'due south lightbulb moment was powerful. She was listening to her friend and walked away with a deeper inferential understanding, becoming aware that the author was conveying a message beyond just the surface story. These sorts of incidents occurred frequently and supported students' abilities as a community to construct meaning. With smaller groups (no more than than v children) and give-and-take norms in place, the children were more successful. As the year progressed, they required less support. Providing children with strong scaffolds and giving them space to hold meaningful discussions taught them to listen; more important, it taught them to intendance most what others had to say and to learn from each other. Ultimately, collaborative conversations helped students find their voices.

Speaking and listening leads to learning

Throughout the year, the children demonstrated deeper literary understandings because they spoke and listened to each other. One day, later on taking a reading assessment required by the school district, Meridith overheard the children talking about how like shooting fish in a barrel information technology was. Eloise explained why: "They didn't even enquire usa to infer!"

At the finish of the school yr, Meridith summed up her experience:

When children participate in collaborative conversations, they use more inferential thinking as opposed to literal recall of the text. Since I began initiating collaborative conversations, I accept noticed that the children take more risks and share ideas beyond what is right there in the text. Without these conversations, we miss the opportunity to address social injustices, share life experiences, and express compassion and empathy.

When I think about whether or not literature discussions are effective, I retrieve about the moments that would never have happened had we not given students the chance to talk in an surround that truly nurtured and valued student voice. Mateo might never have discovered his love for megalodons, Alexis might even so be searching for the author's message, and Maria might have gone the whole twelvemonth without sharing a unmarried idea. Information technology's not so much about the routines and procedures, but more about what the routines and procedures allow you to accomplish.

Nosotros identify swell value on encouraging, nurturing, and sharing young children'southward voices. Children's thinking and meaning-making experiences with texts bring richness and date to literacy. Throughout this yearlong collaborative study, nosotros identified important strategies for supporting the development of speaking and listening skills with outset-grade students. These instructional ideas provided opportunities for supporting deeper literary conversations with and among young learners.

References

Biffle, C. 2013. Whole Encephalon Teaching for Challenging Kids (and the Rest of Your Class, Besides!). Yucaipa, CA: Whole Brain Teaching LLC.

Baker, L., Chiliad.J. Dreher, & J.T. Guthrie, eds. 2000. Engaging Young Readers: Promoting Accomplishment and Motivation. Solving Problems in the Didactics of Literacy series. New York: Guilford.

Carrison, C., & G. Ernst-Slavit. 2005. "From Silence to a Whisper to Agile Participation: Using Literature Circles with ELL Students." Reading Horizons 46 (2): 93–113.

Clay, M.M. 1991. Becoming Literate: The Construction of Inner Control. second ed. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hall, N. 1987. The Emergence of Literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Harvey, Southward., & H. Daniels. 2015. Comprehension & Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding. Rev. ed. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Johnston, P.H. 2004. Choice Words: How Our Language Affects Children'south Learning. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse.

Kelley, M.J., & N. Clausen-Grace. 2013. Comprehension Shouldn't Exist Silent: From Strategy Instruction to Educatee Independence. second ed. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Kelly, Fifty.B., & L. Moses. 2018. "Children's Literature That Sparks Inferential Discussions." The Reading Teacher 72 (1): 21–29.

Kirkland, Fifty.D., & J. Patterson. 2005. "Developing Oral Linguistic communication in Primary Classrooms." Early on Childhood Education Periodical 32 (half-dozen): 391–95.

Moses, L., Thousand. Ogden, & 50.B. Kelly. 2015. "Facilitating Meaningful Discussion Groups in the Primary Grades." The Reading Teacher 69 (2): 233–37.

NGA (National Governors Association Middle for Best Practices) & CCSSO (Council of Chief State School Officers). 2010. Common Core State Standards. Washington, DC: NGA & CCSSO.

Nystrand, M. 2006. "Research on the Role of Classroom Soapbox as It Affects Reading Comprehension." Research in the Teaching of English 40 (4): 392–412.

Serafini, F. 2009. Interactive Comprehension Strategies: Fostering Meaningful Talk about Text. New York: Scholastic Educational activity Resources.

Wells, G. 1999. Dialogic Inquiry: Towards a Sociocultural Practice and Theory of Education. Learning in Doing: Social, Cerebral, and Computational Perspectives series. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Photographs: 1, three © Getty Images; ii courtesy of the authors

campbelloffam1958.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/mar2019/speaking-listening-primary-grades

0 Response to "Strategies for Helping Kids Remember What They Read Using Stickies"

Post a Comment